|

The

Origin of a Myth:

Mary Shelley's Novel Frankenstein

Download

the complete text here

(ZIP archive 161KB)

or

click here for a

short summary of the novel

Portrait of Mary Shelley

|

The life of a monster creator:

Mary Shelley's

biography

Even before she was born,

Mary Shelley (1797-1851) was destined to become one of the most prominent figures

in English literature. Both her parents

were revolutionaries and writers: Her father William Godwin (1756-1836) was an

English journalist and novelist and one of the major proponents of

anarchist philosophy. His most famous works were An Enquiry

Concerning Political Justice, an attack on political

institutions, and The Adventures of Caleb Williams, which

attacks aristocratic privilege.

Mary's mother Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797), one of the earliest

feminists, was equally radical. In her book A Vindication of the

Rights of Women Wollstonecaft argues that the inferior role of

women in society was not natural, but rather a consequence of

miseducation. She called for equality of women and men, the women's

right to work and proper education for girls. Although she died ten

days after giving birth to her daughter Mary, her works continued to

influence Mary Shelley.

|

Mary grew up surrounded by intellectual minds and she was educated and

tutored by her father, who married his second wife Mary Jane Clairmont

in 1801.

In 1812 Mary Wollstonecroft Godwin met Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822),

who visited her father at his bookshop. Percy Shelley, a poet and

radical free-thinker, fell in love with Mary, despite being still

married to his first wife Harriet. Mary and Percy both shared a love for

literature and they used to discuss literary classics and philosophy. In

the summer of 1814 they eloped to France, together with Mary's step

sister Jane Clairmont. Mary's father, who had always proclaimed free

love, did not approve of this relationship and did not talk to his

daughter for more than a year.

In 1816 Mary and Percy travelled to Switzerland, where Mary conceived Frankenstein. They got married on December 30, after Percy's first wife

Harriet had comitted suicide.

This was followed by a period of constant moving, first in England,

later in Italy, which was overshadowed by the death of Mary's children

Clara and Will. On 8 July 1822 - the Shelleys had moved to Pisa earlier

- Percy

Shelley died in a sailing accident. Mary was left with her only

surviving child Percy Florence Shelley and spent the rest of her life in

England promoting her late husband's work. She also continued her own

literary career. In 1826 she published The Last Man, a science

fiction novel about a post-apocaclyptic world ravaged by a terrible

plague, which became her second-best known book.

Mary Shelley continued to be surrounded by prominent figures of

literature and art, but at the same time was met with hostility and

disapproval from more conventional circles. She died on 1 February 1851.

Mary Wollstonecraft

William Godwin

Percy Bysshe Shelley

Creating a legend: The

summer of 1816

The

origin of Frankenstein

is

almost as mysterious and exciting as the novel itself. It all began

back in the summer of 1816 at the famed Villa Diodati on the shores

of Lake Geneva, Switzerland, where Mary Shelley spent

most of that summer together with her future husband Percy Bysshe

Shelley, her stepsister Claire Clairmont, Lord Byron and Dr. John

Polidori, Byron's physician. Inspired by a reading of the Fantasmagoriana, a collection of German ghost stories, on June 16

they decided to try their hands on supernatural stories themselves.

The first one to come up with a story was Polidori, who began

his now famous tale The Vampyre. Its main protagonist Lord Ruthven was

supposedly modeled on Lord Byron. However, Mary Shelley was not that

quick in creating her first piece of literature. Initially, she suffered

from some kind of writer's block and produced nothing so far until one day she

had (or claimed to have) a sort of vision that finally inspired her to write

Frankenstein.

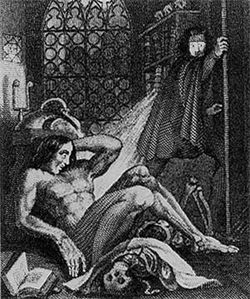

She described this vision in the preface of the novel:

"I

placed my head on my pillow, I did not sleep, nor could I be said to

think. My imagination unbidden, possessed and guided me.. I saw with shut

eyes, but acute mental vision, - the pale student of unhallowed arts

standing before the thing he had put together, I saw the hideous phantasm

of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine,

show signs of life and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion... frightful

must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human

endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world.

His success would terrify the artist; he would rush away from his odious

handiwork, horror stricken.... He (the artist) sleeps but he is awakened;

he opens his eyes; behold, the horrid thing stands at his bedside, opening

his curtains and looking on him with yellow, watery, but speculative

eyes."

A

couple of days later, Mary Shelley finally began to write her own ghost

story that would then become chapter IV of Frankenstein. She completed

the novel in 1817 and the first edition was

published anonymously in 1818, with a preface by Percy Shelley. (A brief summary is available here.)

Only 500 copies were printed and the novel

was split in three parts. Although historical novelist Walter Scott,

author of Ivanhoe, liked Frankenstein and wrote "the

work impresses us with a high idea of the author's original genius and

happy power of expression", most reviews at the time were rather unfavourable.

The Quarterly Review wrote the following in 1818:

"Our taste and our judgement

alike revolt at this kind of writing, and the greater the ability with

which it may be executed the worse it is -- it inculcates no lesson of

conduct, manners, or morality; it cannot mend, and will not even amuse

its readers, unless their taste have been deplorably vitiated"

Still,

the novel had already become quite popular and had even

spawned several theatrical adaptations, the best known of them

Brinsley Peake's Presumption.

A second edition (this time credited to Mary Shelley) was published in

1823 in two volumes.

In October 1831 a revised edition of Frankenstein was published in one

volume. Mary Shelley had made several changes to this version: She added

a longer preface, Victor Frankenstein was portrayed as a more benevolent

character and indications of an incestuous relationship between Victor

and Elizabeth were removed by clearly marking her as the adopted child

of the Frankensteins.

Frontispiece illustration to 1831 edition of Frankenstein

When Mary Shelley composed Frankenstein, she was influenced by several

literary classics she had read with her future husband Percy. She

references these works in Frankenstein, among them Ovid's Metamorphoses

and John Milton's Paradise Lost.

At one point in the novel, the monster says,

after reading Paradise Lost, he sympathizes with Satan's role in the

story:

"But Paradise Lost excited different

and far deeper emotions.

[...] Like Adam, I was apparently united by no link to any other being

in existence; but his state was far different from mine in every

other respect. He had come forth from the hands of God a perfect

creature, happy and prosperous, guarded by the especial care

of his Creator; he was allowed to converse with, and acquire

knowledge from, beings of a superior nature: but I was wretched,

helpless, and alone. Many times I considered Satan as the fitter

emblem of my condition; for often, like him, when I viewed

the bliss of my protectors, the bitter gall of envy rose within me."

The name Frankenstein was probably taken from a castle near the German

town of Darmstadt, where Mary and Percy had travelled through on their

way from Basel. According to a highly disputed theory by German

historian Walter Scheele, Mary had heard of Johann Konrad Dippel, a

German alchemist, who had lived at Burg Frankenstein in the early 18th

century. Legend has it that Dippel experimented with dead bodies and was

able to create an artificial monster, just like Victor Frankenstein.

Additionally, alchemy and galvanism were popular topics at the time and

Mary knew about them.

One particularly interesting influence is the Swiss painter Henry Fuseli,

who once had a relationship with Mary's mother, that lasted four years.

Fuseli's painting The Nightmare

inspired the description of Elizabeth's dead body flung across her

bridal bed just after her murder by the creature in chapter 23:

"She was there, lifeless and inanimate,

thrown across the

bed, her head hanging down, and her pale and distorted features

half covered by her hair. Everywhere I turn I see the same

figure--her bloodless arms and relaxed form flung by the

murderer on its bridal bier."

The Nightmare by Henry Fuseli (1781-82)

What to do with a monster: Interpreting

Frankenstein

But what

exactly was it that Shelley wanted to express with Frankenstein

? Does she condemn the protagonist Victor Frankenstein for his hubris or

does she approve of his deeds? Due to the fact that throughout the novel Frankenstein,

Mary Shelley never explicitly comments on her position, Frankenstein is an

open invitation for all sorts of theories and interpretations. The following

section is dedicated to these questions and presents a number of possible

different interpretations of Frankenstein based on the work of

several critics.

These different readings of Frankenstein, on the one hand

conservative criticism on science, on the other hand the Promethean

believe in the unlimited progress of science, are based on the three

different narrators of the novel. Two contradicting points of view are

expressed in the narratives of Frankenstein and the Monster, whereas

Walton's frame narrative basically supports Victor Frankenstein's point of

view. Therefore the value of Mary Shelley's novel lies not in presenting a

clear morale but in encouraging the readers to make up their own.

Victor

Frankenstein's original reasons for creating life from dead parts are

noble. His driving force is the desire to help mankind conquer death and

diseases. But when he finally reaches the goal of his efforts and sees his

creature and its ugliness, he turns away from it and flees the monstrosity

he has created. From that moment on he tries to suppress the consequences

of his experiments and wants to escape them by working in other sciences.

Victor even withdraws from his friends and psychological changes are

visible.

Mary Shelley seems not to condemn the act of creation but rather

Frankenstein's lack of willingness to accept the responsibility for his

deeds. His creation only becomes a monster at the moment his creator

deserts it (1). Thus Frankenstein warns of the

careless use of science - the book was written at an early stage of the

Industrial Revolution, a period of dramatic scientific and technological

advance. This is still an important issue, even 200 years

after the book was written. Taken into consideration what many inventions

of the last 50 years brought upon mankind, one must assume that many

scientists still do not care much. (E.g. the splitting of the atom was

turned into nuclear bombs and the invention of the computer resulted in an

eerie dehumanisation of our society). Most scientists seem to be like

Victor Frankenstein, who finished his work in the prospect of achieving

fame. Only when he realizes the repulsiveness of his creation, Victor

comes to senses. Intended as a warning, Victor tells his story to the

polar explorer Walton:

"I

will not lead you on, unguarded and ardent as I then was, to your

destruction and infallible misery. Learn

from me, if not by my precepts, at least by my example, how dangerous is

the acquirement of knowledge, and how much happier that man is who

believes his native town to be the world, than he who aspires to become

greater than his nature will allow." (Shelley: 51-52)(2)

In his corrupting pursuit for knowledge Victor Frankenstein is compared

to Prometheus, as the novel's subtitle "The Modern Prometheus"

suggests. In Greek and Roman mythology, the Titan Prometheus creates

mankind as an image of the Gods. Later he steals the precious fire form

Olympus and gives it to mankind. He is punished by Zeus, who has him

chained to Mount Cauasus, where day by day an eagle would eat out his

liver, which would then grow back. It is a typical example of "hubris", where a character

is doomed because he transgresses his limits and rises up against some

sort of authority, in Greek mythology usually a divine authority. The

mythological Prometheus rebelled against the Gods when he gave fire to

humankind; Frankenstein is a rebel against nature when he tries not only

to find the secret of life but also to remove life's defects (3).

But even more so, in Victor Frankenstein both aspects of the Prometheus

myth are embodied: the transgressive (hubris/rebellion against authority)

and the creative (Prometheus also molded mankind from pieces of clay).

Therefore Frankenstein is truly a drama of the romantic promethean

hero who fails in his attempt to help mankind.

Feminist literary theory claims that Frankenstein's act of creation

is not only a sin against God/nature. It is also an act against the "female

principle", which includes natural procreation as one of its central aspects. The Monster, the result of male arrogance, is the enemy and

destroyer of the eternal female principle (4). The

Monster is the child of an unnatural act of procreation in which woman has

become unnecessary. The male, who is the executive power in a patriarchal

system, has deprived woman of her most natural function because he is now

able to

create children without female participation. The present discussion about

genetic engineering and human cloning shows that this is not a far-fetched

utopia.

At

least in his subconscious Frankenstein must have realised his crime

against the "female principle", which becomes clear in the

following symbolic dream. In the night after the reanimation of the

Monster Victor has a nightmare in which he kills his mother and his fiancée: |

Frankenstein creates the

fiend - illustration by

Bernie Wrightson (© 1977) |

"I

thought I saw Elizabeth, in the bloom of health, walking in the streets of

Ingolstadt. Delighted and

surprised, I embraced her; but as I imprinted the first kiss on her lips,

they became livid with the hue of death; her features appeared to change,

and I thought that I held the corpse of my dead mother in my arms; a

shroud enveloped her form, and I saw the grave-worms crawling in the folds

of the flannel. " (Shelley: 57) (2)

At

the same time Frankenstein is not willing to fully take the role of the

mother of his "child". Immediately after its birth he leaves his

child and thereby evades his parental duty to care for the child.

Walton,

constructed as a parallel to Frankenstein, is kept from continuing his

dangerous journey by Frankenstein's cautionary tale. But in contrast to Walton

Frankenstein's character remains somehow ambivalent. Although he feels

remorse for his deeds he ends his tale with a rather strange statement:

"Farewell,

Walton! Seek happiness in

tranquillity and avoid ambition, even if it be only the apparently

innocent one of distinguishing yourself in science and discoveries. Yet why do I say this? I have myself been blasted in these

hopes, yet another may succeed." (Shelley: 210) (2)

Victor

Frankenstein has given up his attempts to create artificial life. But he still hopes that

someone else may successfully continue his works. This last sentence makes

all his warnings look like a farce. And it also brings up the assumption

that Mary Shelley really did not condemn the Promethean striving of her

hero. Probably she was not against scientific progress but only wanted to

warn of carelessness in science.

A

totally different position is represented in the Monster's narrative, the

central part of the novel. If only this narrative is considered, the

Monster appears to be an almost perfect creation (apart from his horrible

appearance), who appears often more human than the humans themselves. He is

benevolent (he saves a little child; he helps the De Lacey family

collecting firewood), intelligent and cultured (he learns to read and talk

in a very short time; he reads Goethe's Werther,

Milton's Paradise Lost and Plutarch's works). The only reason why he fails is his

repulsive appearance. After having been rejected and attacked again and

again by everyone he encounters only because of his horrible physiognomy,

the Monster, alone and left on his own, develops a deadly hatred against

his creator Frankenstein and against all of mankind. Therefore only

society is to blame for the dangerous threat to mankind that the Monster

has become. If people had

adopted the Monster into their society instead of being biased against

him and mistreating him he would have become a valuable member of the

human society due to his outstanding physical and intellectual powers.

Mary

Shelley's husband, the romantic poet Percy B. Shelley, saw Frankenstein as a summing up of one of the central ideas of the

enlightenment movement. The moral qualities and faults of a human being

are mainly the products of his/her private and social environment (5). Everything we become is simply a question of nature

vs. nurture. In his review "On Frankenstein" (1818)

Percy B. Shelley wrote:

"Nor

are the crimes and malevolence of the single Being, though indeed

withering and tremendous, the offspring of any unaccountable propensity to

evil, but flow irresistibly from certain causes fully adequate to their

production. They are the children, as it were, of Necessity and Human

nature. In this the direct morale of the book consists, and it is perhaps

the most important and of the most universal application of any morale

that can be enforced by example - Treat a person ill and he will become

wicked. Requite affection with scorn; let one being be selected for

whatever cause as the refuse of his kind - divide him, a social being,

from society, and you impose upon him the irresistible obligations -

malevolence and selfishness. It is thus that too often in society those

who are best qualified to be its benefactors and its ornaments are branded

by some accident with scorn, and changed by neglect and solitude of heart

into a scourge and a curse."

For Percy Shelley the problem does not seem to be Frankenstein's promethean

transgression because danger for mankind is not rooted in science but in

society itself. In this context Frankenstein's final words become quite

clear: Someone else should continue his experiments and remove the

creature's visible defects, in other words assemble a creature with a more

beautiful appearance, which would be accepted by society more easily. If

this could be achieved, the result would be the perfect artificial human

being.

At

this point other critics continue and read Frankenstein in a different context. To

them the book works as a harsh criticism on religion. (6) The horrible physiognomy of the Monster is

only a result of Frankestein's hurry and anxiety caused by his awareness

of committing a sin against God. Because of this unrest he uses inadequate

materials and assembles them too quickly. It implies that a scientist can

only work for the benefit of mankind if he breaks with the church and its

values. This reading of Frankenstein may have been influenced by Percy

Shelley's pamphlet "The Necessity of Atheism" (1810), where he

states that a reasoning human being has to deny the existence of God due

to a lack of proofs. However, one might easily share my opinion that this interpretation of Frankenstein

is a bit far-fetched. Since Victor Frankenstein is not at all a

professional surgeon he cannot be expected to create a perfect human being

out of partly rotten body parts, especially not with the kind of

instruments, assistance and funding he uses.

In

her preface to Frankenstein Mary

Shelley admits that her main goal was simply to write a ghost story. She got the

idea for what she later called her "hideous progeny" during the

legendary summer of 1816, which she spent at Lake Geneva in Switzerland

together with Percy Shelley, Lord Byron and Dr. John Polidori. Inspired by

Fantasmagoriana, a French translation of German Gothic tales, they

held some kind of ghost story competition where Mary Shelley invented her

story of Frankenstein.

But

the classification of Frankenstein

as a ghost story, Gothic novel or horror novel is not fully adequate,

considering the following facts: It

contains no supernatural apparitions such as ghosts, witches, devils, demons

or sorcerers. In Frankenstein

all "diabolical agency has been replaced by human, natural and

scientific powers" (7). Other typical Gothic elements,

e.g. ruined castles, graveyards and charnel houses, appear only briefly or

in the distance. And unlike most Gothic novels Frankenstein

is set in the 18th rather than in the 15th century.

Shelley also abandoned the simple good-evil scheme of the Gothic novel. Neither

Frankenstein nor the Monster are one hundred percent good or evil. Instead

they are both highly ambivalent characters. Frankenstein

is rather a kind of novel German literary critics call

"Entwicklungsroman", a form of the novel showing the development

of an individual's character. Both Victor and his creation change during

the novel as a consequence of their relationship. Furthermore, one could

argue that it shows the Monster's development from earliest childhood to

adulthood. And by making its protagonist hero as well as victim Frankenstein

is clearly set in the context of Romanticism.

The

Frankenstein monster as a symbol for cloning: Cartoon on stem cell

research by Dick Wright (© 2001)

But

since one of its main topics is a scientific discovery, Frankenstein

could equally be called a precursor of the science fiction novel. The

artificially created Monster is often seen as a foreshadowing of recent

scientific developments like test-tube babies, robots and organ

transplantation. The Monster may also be interpreted as "a symbol of

the ambiguous nature of the machine" (8) or as a symbol

of modern technology.

© 2000 -2007

Andreas Rohrmoser

Footnotes:

1 cf. Weber, Ingeborg, "Doch einem mag es gelingen".

Mary Shelley's “Frankenstein“: Text, Kontext, Wirkung; Vorträge des

Frankenstein-Symposiums in Ingolstadt (Juni 1993). Ed. Günther

Blaicher (Essen: Verlag Die Blaue Eule, 1994) 24

2 Page numbers in quotations from Mary

Shelley's Frankenstein refer to the following edition:

Shelley, Mary: Frankenstein. (London: Penguin Books, 1992)

3 cf. Gassenmeier, Michael, "Erzählstruktur,

Wertambivalenz und Diskursvielfalt in Mary Shelleys Frankenstein".

Mary Shelley's “Frankenstein“: Text, Kontext, Wirkung; Vorträge des

Frankenstein-Symposiums in Ingolstadt (Juni 1993). Ed. Günther

Blaicher (Essen: Verlag Die Blaue Eule, 1994) 42

4 cf Markus, Manfred, "Mary Shelleys Frankenstein aus

biographischer Sicht".

Mary Shelley's “Frankenstein“: Text, Kontext, Wirkung; Vorträge des

Frankenstein-Symposiums in Ingolstadt (Juni 1993). Ed. Günther

Blaicher (Essen: Verlag Die Blaue Eule, 1994) 61

5 cf Gassenmeier 1994: 28

6 cf Gassenmeier 1994: 43

7 Botting, Fred, Gothic (London: Routledge, 1996) 103

8 Baldick,

Chris. In Frankenstein's Shadow: Myth, Monstrosity, and

Nineteenth-Century

Writing.

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990) 7

|